The author’s mother, Ritsu Saimoto (Enjo), attended school in the East Lillooet Internment Camp,

c. 1948-49.This photo was taken on her high school graduation day. The simple gown, paired with long gloves and a single string of pearls, was made by the author’s grandmother, who was a seamstress.

「お帰り」

I remembered my mother’s stories on a glorious day in May 2018 during the unveiling of the East Lillooet Internment Memorial Sign and Garden, as sacred First Nations drumming called the spirits of our Japanese Canadian ancestors to come “home.” Set on the east side of the Fraser River, this swath overlooks the former Internment camp, now a private farm. Against a palette of blue sky, with mountains hugging the east and west side of the mighty Fraser, I could feel the spirits of my grandparents join us. I felt the deep embrace of the spirit of “home.”

Born in Vancouver in the 1930s, my mother lived with her family at the back of my grandparents’ dry-cleaning shop on Main Street. My grandparents emigrated to Canada in the 1920s with dreams of riches and adventure. In 1942 with the escalation of the Second World War, they were, along with all Canadians of Japanese descent, forcibly uprooted to deserted farm fields and ghost towns, stripped of their houses, businesses, boats, and properties—stripped of their civil rights.

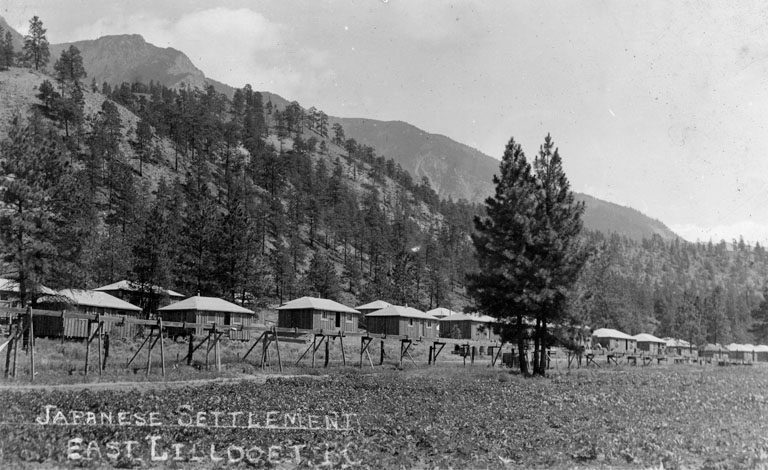

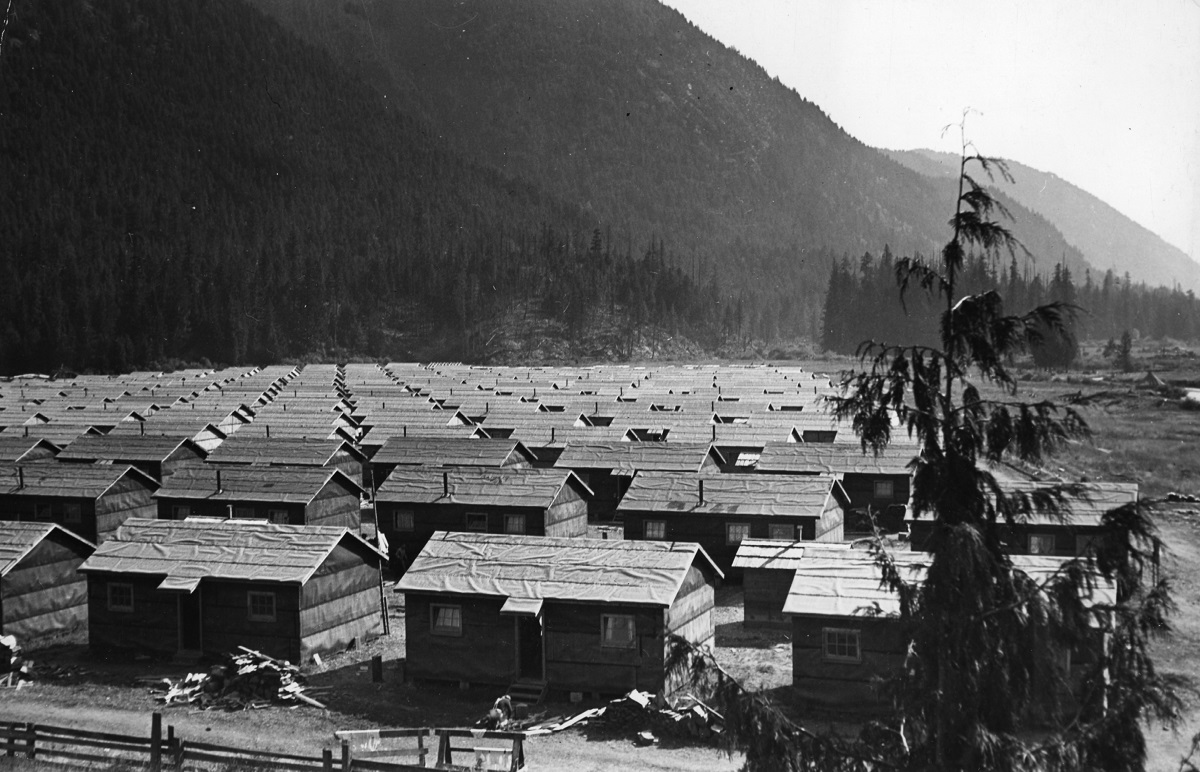

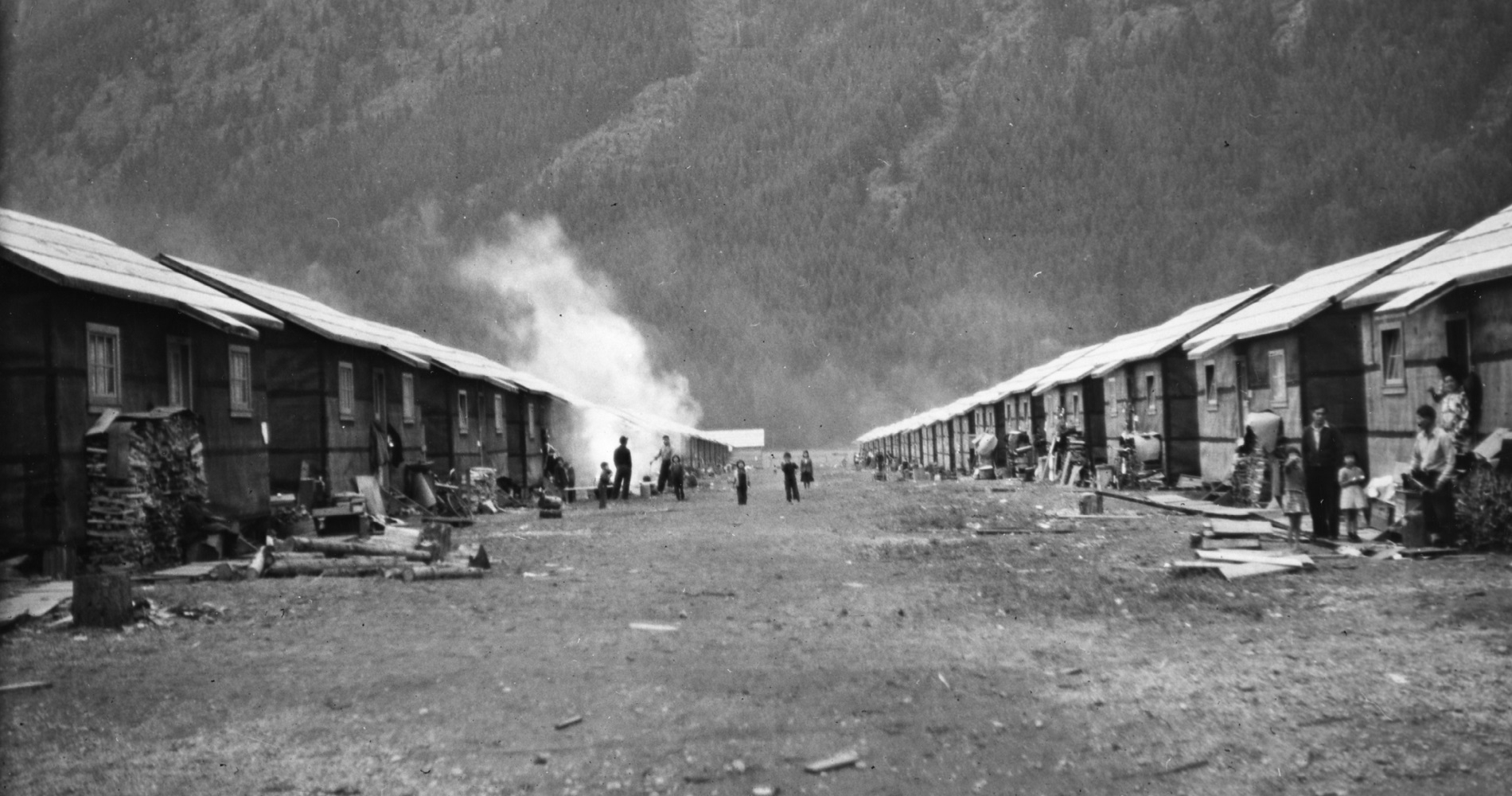

East Lillooet self-supporting internment camp, c. 1942, Nikkei National Museum 1994-52-22 | Trains transporting internees to the Greenwood Internment Camp, Greenwood, 1942, Nikkei National Museum 2011-83-1-33 | Forced relocation of Japanese Canadians to camps in the interior of British Columbia, 1942, Nikkei National Museum 1994-76-3

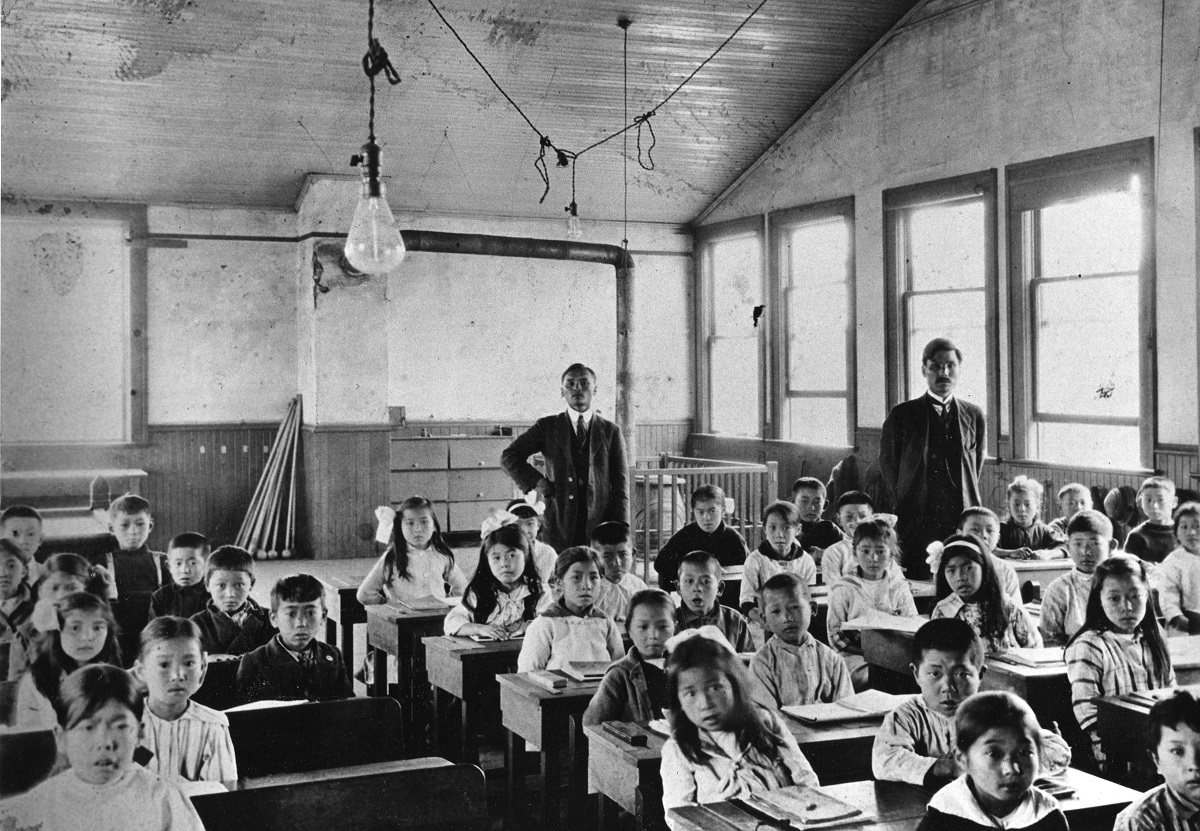

Life in the East Lillooet Internment was fraught with hardships: My mother’s family lived in a one-room tar-paper shack and attended a single-room Japanese children-only school. As a girl, my mom picked tomatoes in the summer heat for 25 cents an hour. In -30-degree winters, icicles formed inside their shack. There was no indoor plumbing or electricity, just a wood stove.

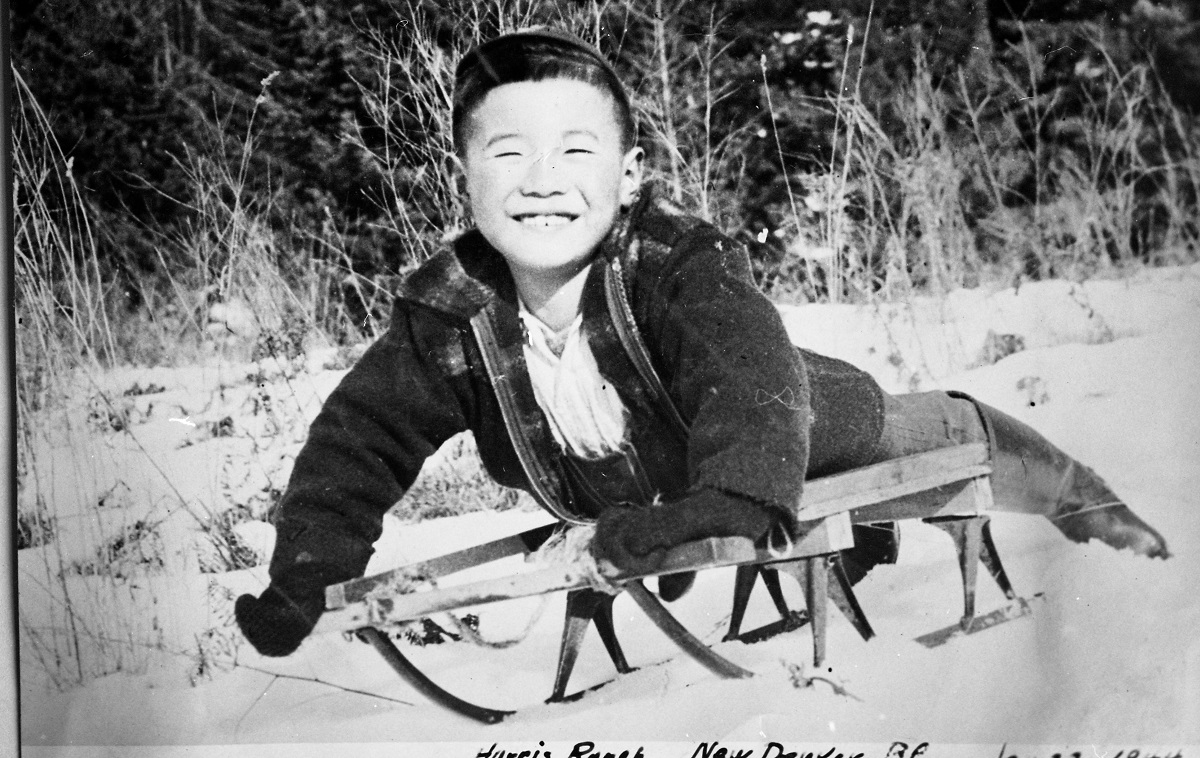

But when I listened to the stories and looked at archival and family photos, one thing struck me: the children, especially, look happy and well-dressed. For my grandparents, who carried the weight of feeding the family, life was physically and emotionally tough. But the community worked together to rebuild. They created a vibrant and creative life for all. From May Queen festivals, baseball games, and even parades to building their own schools and starting their own boy scout troop, they nurtured “the feeling of home,” seen in the faces of the children.

Basil Izumi at Nelson Ranch, New Denver area Internment Camp, Nikkei National Museum 2012-29-2-2-23 | First Tashme Boy Scout Group, February 25, 1945, Tashme Internment Camp. This was one of the largest boy scout troops in North America, Nikkei National Museum 2010-23-2-4-67 | May Day Queen 1946, Lemon Creek Internment Camp, Slocan Valley, Nikkei National Museum 2010-23-2-4-1

While their house and life had vanished overnight, I realized that my family—the entire community, really—had brought their sense of “home” with them, from their hopeful pre-war dreams, through the shock and pain of loss, to the resilient strength of the rebirth of a new kind of home within the camps. I was inspired. I was humbled. I was grateful.

Learn More about pre-war Japanese Canadian life in Metro Vancouver

Living on Main Street, my mother hopped on the street car and attended Japanese School after public school, Monday to Friday. Founded in 1906, this community school supported the children of immigrants, many of whom began to settle and work in the Powell Street area which became known as “Nihon-machi 日本町 (Japan-town).” The restored heritage building remains, and the Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall is now a National Historic Site, offering childcare, language, and culture programs to local residents.

Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall, a National Historic Site in Vancouver, Japanese Hall | Tsutae Sato teaching Japanese language students, 1918, Nikkei National Museum 2010-23-2-4-677 | Schoolgirls in front of the Japanese school, c. 1930s, Japanese Hall

For more discovery, visit the Joy Kogawa House in Vancouver’s Marpole neighbourhood, once the childhood home of the acclaimed author who has worked to educate the public about the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. In Burnaby, the Nikkei National Museum showcases the contribution of Japanese Canadians through public programs, exhibits, and more.

as the heart flies

straight home

home

Joy Kogawa

A Verse Map of Vancouver (2009)

The Gulf of Georgia Cannery | Britannia Shipyards National Historic Site, Tourism Richmond | The bath at the Murakami House at the Britannia Shipyards National Historic Site, Carla Mont

Continue your exploration at National Historic Sites in Steveston with visits to the Gulf of Georgia Cannery and the Britannia Shipyards, both showcasing the role of Japanese Canadians in the West Coast fishing industry. To linger longer, consider visiting the Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society building at the Steveston Museum to learn about how the Japanese Canadian community helped shape the community.

Road Trip Beyond the City Lights; Look for Legacy Signs

You can go beyond the Vancouver skyline for further exploration; keep an eye out for Highway Legacy Signs, installed by the provincial government and local communities in 2018 to recognize where 22,000 Japanese Canadians were interned from 1942-1949.

To start, travel Highway #1 to the Sunshine Valley Tashme Museum, just outside Hope on Highway #3. (You’ll see the Hope Princeton Road camp Highway Legacy Sign at a large pullout about halfway to Tashme.) Built on a dairy farm, the Tashme internment camp was the largest such facility; here, 2,600 Japanese Canadians were interned. Museum founder Ryan Ellan converted the original butcher shop into a museum, showcasing what it was like to live and work in the camp, and even what families did for fun (a reconstruction of a tar-paper internment shack is also part of the experiential exhibit).

Tashme Internment Camp (outside Hope), c. 1942, Nikkei National Museum 1994-69-4-28 | Unveiling of the Tashme Internment Camp Highway Legacy Sign, Sunshine Valley, Oct. 27, 2017, Sunshine Valley Tashme Museum | Sunshine Valley Tashme Museum, Sunshine Valley outside Hope, July 2020, Sunshine Valley Tashme Museum

Northwest towards Lillooet, road trippers will find the aforementioned East Lillooet Internment Memorial Garden, home to a stone memorial monument dedicated to the families interned here. In town, visit other Japanese Canadian historic sites, including the “Forbidden Bridge,” a suspension bridge across the Fraser that connected Japanese Canadians to a white township. (Japanese Canadians were not allowed to cross into the township, and it would take friendly baseball games between the two communities to thaw this racial divide.)

East Lillooet Internment Memorial Garden, Lillooet, July 2020, Laura Saimoto | The "Forbidden Bridge," now a pedestrian bridge connecting the east to west side of the Fraser River, Lillooet, Laura Saimoto | East Lillooet Memorial Monument dedicated to the Internee families located in the Memorial Garden, May 2018, Saimoto family

To road trip beyond Tashme, travel along Highway #3 to the Greenwood Museum; keep an eye out for the Highway Legacy Sign across the street. At the museum, you can discover how Greenwood, a copper mining ghost town, became an internment site.

Heading towards Nelson, take Highway #6 north to the Slocan Valley and Kootenay Rockies, an area that housed the largest concentration of interned Japanese Canadians: nearly half of the 22,000 sent to camps. The Slocan Extension Sign (pullout on Highway #6) tells the story of Slocan City, Lemon Creek, Popoff, and Bayfarm internment sites, which were built on open farm fields.

Continuing on Highway #6 to the small village of New Denver, stop in at the New Denver Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre, a National Historic Site. Here, original internment camp shacks have been lovingly preserved in an outdoor memorial park complete with a Japanese Garden.

The scenic drive along Highway# 6 will also take you to the historic town of Kaslo, which, like the ghost town of Greenwood, was converted into an internment camp (another Highway Legacy sign welcomes visitors to the town). While here, visit the Langham Museum to learn about the Japanese Canadian experience.

On the Upper Arrow Lake ferry, it’s a short hop to Revelstoke. This journey is stunning—a true hidden secret in the Kootenay Rockies. From Revelstoke, visit Three Valley Gap, where the Revelstoke-Sicamous road camp Highway Legacy Sign is located on the north side of Highway #1, overlooking a stretch of highway that was constructed by Japanese Canadian men.

I’ve been to these sites, and this experience has deepened what home, and being a Canadian, means to me.

In 1949, the War Measures Act was lifted and the Citizenship Act was passed, granting all Canadians citizenship and the right to vote, regardless of race. (All information you can learn when you visit the sites.)

After seven long years, all civil rights were restored to Japanese Canadians. They could return “home.” For many, that meant starting over. For me, I ask “what is home?”—past and future—as a British Columbian, a Canadian, and a global citizen.

Header image: Tashme Internment Camp, just outside the 100 mile Exclusion Zone, 10 miles outside Hope, c. 1942 | Nikkei National Museum 1994-69-4-28

Start Planning Your BC Experience

Getting Here & Around

Visitors to British Columbia can arrive by air, road, rail, or ferry.

Visit TodayAccommodations

Five-star hotels, quaint B&Bs, rustic campgrounds, and everything in between.

Rest Your Head